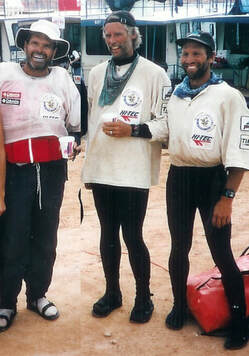

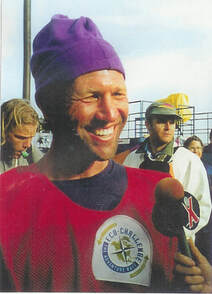

Dr. Bob, Mace, Marsh 1995 Eco Utah finish.

Dr. Bob, Mace, Marsh 1995 Eco Utah finish.

At 44 years old, I knew nothing about adventure racing, but jumped at the chance to race the first Eco in Utah in 1995.

At 44 years old, I knew nothing about adventure racing, but jumped at the chance to race the first Eco in Utah in 1995.

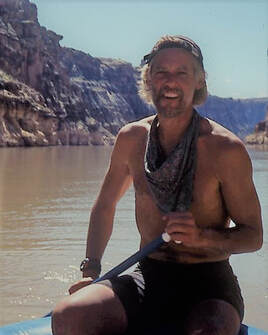

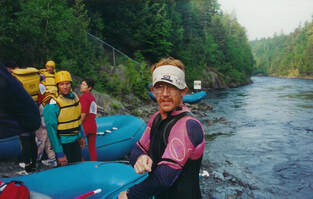

Mace was always a good sport, even when faced with new challenges, like paddling.

Mace was always a good sport, even when faced with new challenges, like paddling.

The Stray Dogs in Class V whitewater in Cataract Canyon.

The Stray Dogs in Class V whitewater in Cataract Canyon.

Marsh and Mace on the ropes.

Marsh and Mace on the ropes.

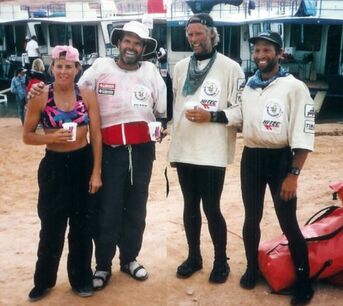

Original Stray Dogs Lisa, Dr. Bob, Mace, and Marsh at the very first Eco-Challenge, Utah 1995.

Original Stray Dogs Lisa, Dr. Bob, Mace, and Marsh at the very first Eco-Challenge, Utah 1995.

Adrian, Tommy, Angelika, Whitt, and Marsh Eco New England 1995.

Adrian, Tommy, Angelika, Whitt, and Marsh Eco New England 1995.

Even though we portaged the canoe part of the way, we still had to paddle.

Even though we portaged the canoe part of the way, we still had to paddle.

The kayaking leg dropped us to 2nd place.

The kayaking leg dropped us to 2nd place.

Note Mark Burnett in the background.

Note Mark Burnett in the background.

Angelika is a true leader.

Angelika is a true leader.

Marsh and Adrian, back in the day.

Marsh and Adrian, back in the day.

Eco BC started on horses.

Eco BC started on horses.

Dr. Bob and I went the "wrong" way during the canoeing section.

Dr. Bob and I went the "wrong" way during the canoeing section.

Marsh, Mace, and Dr. Bob: still Stray Dogs and friends in 2019.

Marsh, Mace, and Dr. Bob: still Stray Dogs and friends in 2019.

The pre-race meeting included an appearance by Steve Irwin, talking about the snakes that could kill us out there!

The pre-race meeting included an appearance by Steve Irwin, talking about the snakes that could kill us out there!

Shaz, Mace, Dr. Bob, and Marsh: how bad are YOUR feet?

Shaz, Mace, Dr. Bob, and Marsh: how bad are YOUR feet?

Marsh, Shaz (and son), Mace, and Dr. Bob at the finish: no one sufferer like Dr. Bob.

Marsh, Shaz (and son), Mace, and Dr. Bob at the finish: no one sufferer like Dr. Bob.

Mace starting the race on a camel.

Mace starting the race on a camel.

The surf was just a small sign of things to come.

The surf was just a small sign of things to come.

Mace stared down every challenge, dead on.

Mace stared down every challenge, dead on.

Marsh, Mace, and Isaac shake hands at the finish.

Marsh, Mace, and Isaac shake hands at the finish.

Marsh, Shaz, Isaac, and Mace walk the red carpet during the closing ceremonies.

Marsh, Shaz, Isaac, and Mace walk the red carpet during the closing ceremonies.

Patagonia is stunningly beautiful.

Patagonia is stunningly beautiful.

Team Captain Louise leading the way.

Team Captain Louise leading the way.

Mace steps out of the kayak.

Mace steps out of the kayak.

They thought we were old at over 50!

They thought we were old at over 50!

Mo, Mace, Marsh, and Adrian check the first set of maps.

Mo, Mace, Marsh, and Adrian check the first set of maps.

Adrian, Marsh, and Mace in Borneo.

Adrian, Marsh, and Mace in Borneo.

One of outriggers used in Borneo.

One of outriggers used in Borneo.

The jungle was tough on Mace, and all the athletes.

The jungle was tough on Mace, and all the athletes.

Mo, Adrian, Marsh, and Mace pre-race.

Mo, Adrian, Marsh, and Mace pre-race.

Stray Dogs men mountain biking, with no trail - of course!

Stray Dogs men mountain biking, with no trail - of course!

Marsh, Mace, Mo, and Adrian at the top of the mountain.

Marsh, Mace, Mo, and Adrian at the top of the mountain.

Sometime rolling with the punches means sleeping whenever and wherever you can!

Sometime rolling with the punches means sleeping whenever and wherever you can!

Dianette during a mountain "biking" river crossing.

Dianette during a mountain "biking" river crossing.

Mace (back) and Marsh trekking through the cold jungle.

Mace (back) and Marsh trekking through the cold jungle.

Adrian and his team entering a village on the dry side of the island.

Adrian and his team entering a village on the dry side of the island.

No matter how cold and miserable he might be, Mace always kept his sense of humor.

No matter how cold and miserable he might be, Mace always kept his sense of humor.

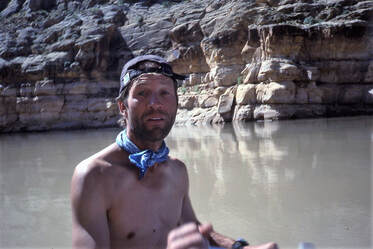

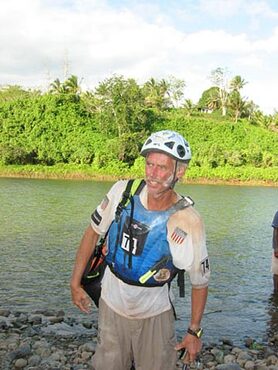

Marshall Ulrich earned those lines of wisdom.

Marshall Ulrich earned those lines of wisdom.